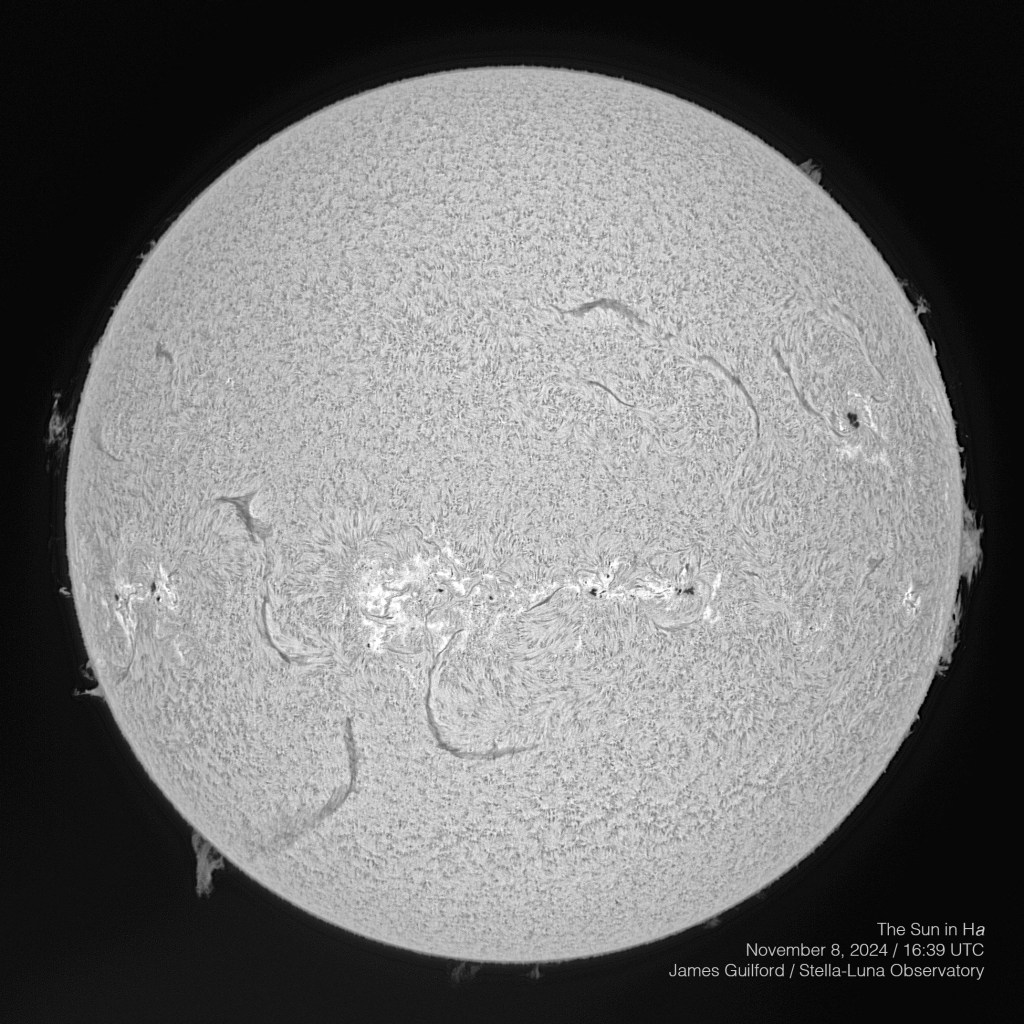

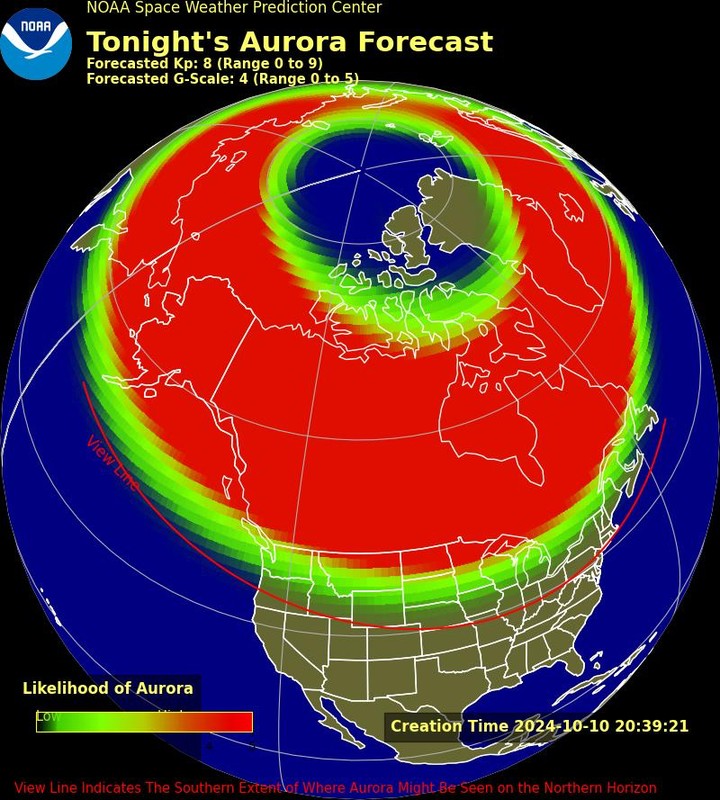

Taking advantage of midday clear skies, Thursday, we set up the hydrogen-alpha telescope and did a little observing and imaging. Seeing conditions were only good but we could make out several prominences along Sun’s limb. (The proms did not record well and we need to figure out how to enhance their visibility in our images.) Most notable, however, was the shear number of filaments in Sun’s northern hemisphere. None visible in the south! Fragments of exploding filaments launched from Sun and produced two CMEs that, when they reached Earth on April 16, caused strong geomagnetic storm activity and widespread auroras. The storm, however, died out before northern lights could be seen here.

Aiding in our efforts was a device we used for the very first time in this session: The Sky-Watcher SolarQuest with its HelioFind system. The device is lightweight, easily supported our rather robust Coronado solar telescope, and was exceptionally easy to learn and operate. Essentially, all that was needed was to set the tripod up so that it was level, turn the device on, and let it do its thing! It is powered by four AA batteries, placed inside the unit. As an alt-az mount, no counterweights or muliti-axis balancing was needed; just mount the scope with its balance point at the center of the dovetail clamp. No remote control, no app, the compact and self-contained SolarQuest established GPS contact, leveled the scope, then looked for Sun. The SolarQuest turned and elevated the telescope, quickly acquiring our nearest star. When the motion stopped, we looked through the eyepiece to discover Sun well within the field of view. A few nudges of the system’s adjustment buttons and Sun was centered. Tracking was excellent throughout the observing/imaging session. Provision is made for further refinement of tracking but that adjustment was unnecessary for the day’s activity. The SolarQuest will make our daytime astronomy a whole lot more convenient and enjoyable!

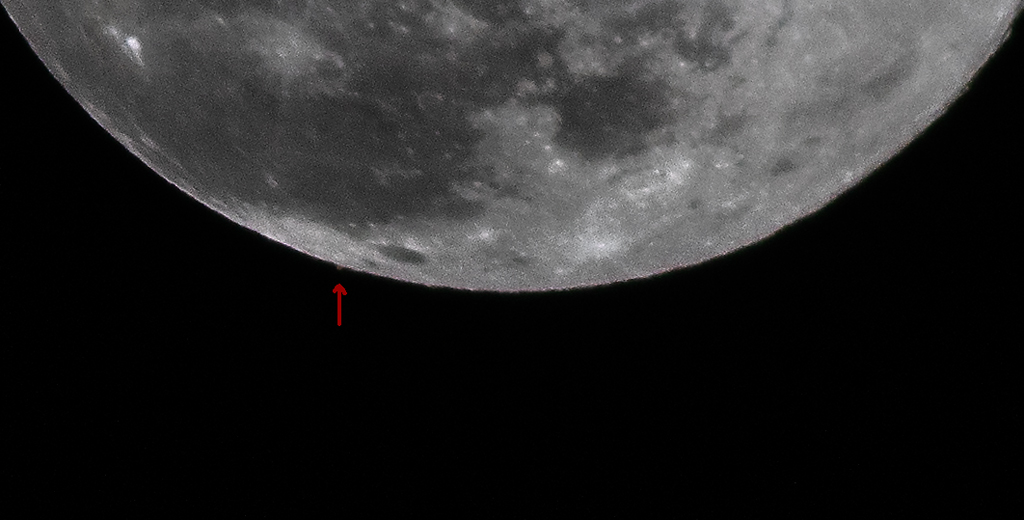

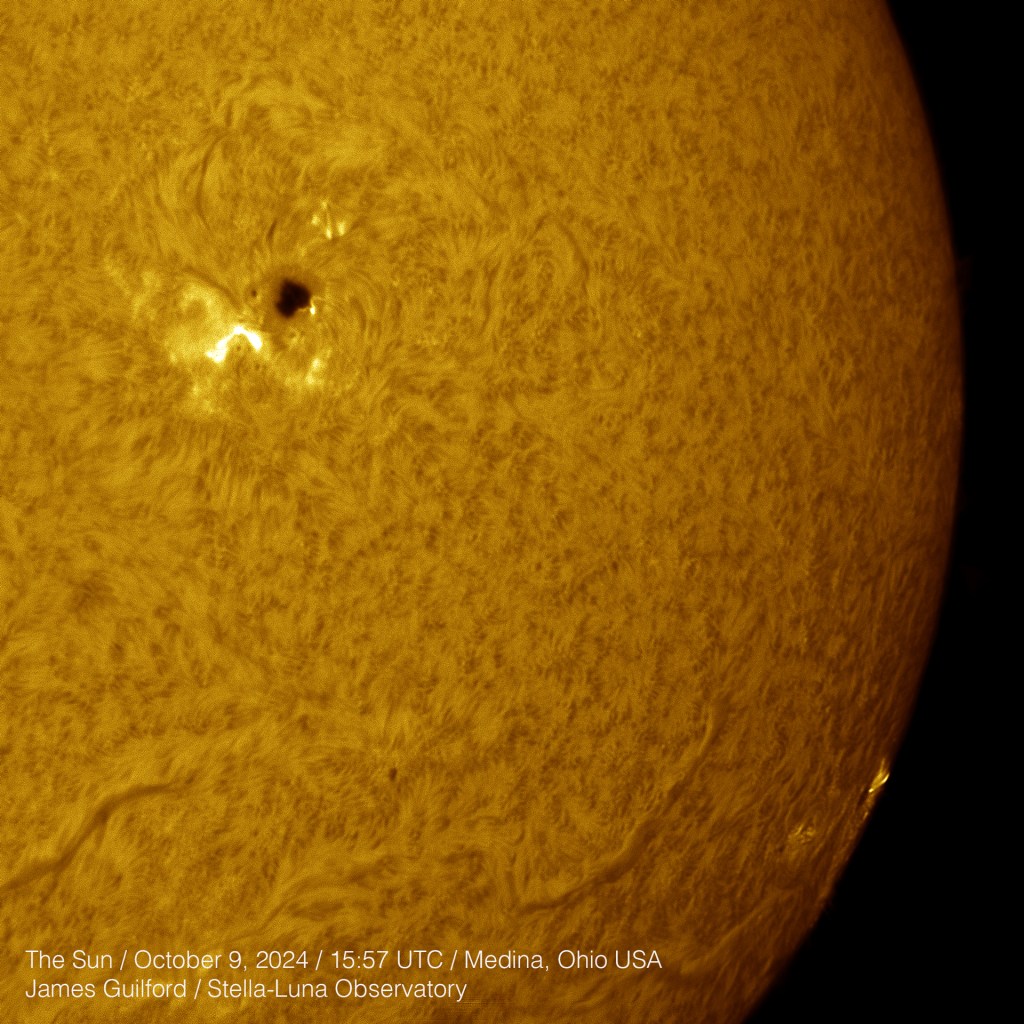

We had just finished setting up for some solar astronomy and tapped the button to begin a video sequence when something flashed across the computer screen. A jet appeared for less than a second, contrails briefly persisting, silhouetted against the roiling solar disk! We’ve only seen this twice while observing Sun, this being the second time, and we only captured this image by shear luck. The first time we witnessed a solar “photo-bombing” was under similar circumstances. Previously, we had completed setup, was refining focus, and just about to begin recording exposures. We missed imaging that encounter by about the same interval as we succeeded this time!