Still working without a dome, our setups are outdoors and temporary so we try and keep them fairly simple. Solar observing and imaging generally lend themselves well to brief observations due to the extreme amount of light available and resultant short photographic exposures. With a couple of clear days and nights available, we took advantage and made some experiments and observations with several successive setups on a single Skywatcher EQ6-R Pro mount.

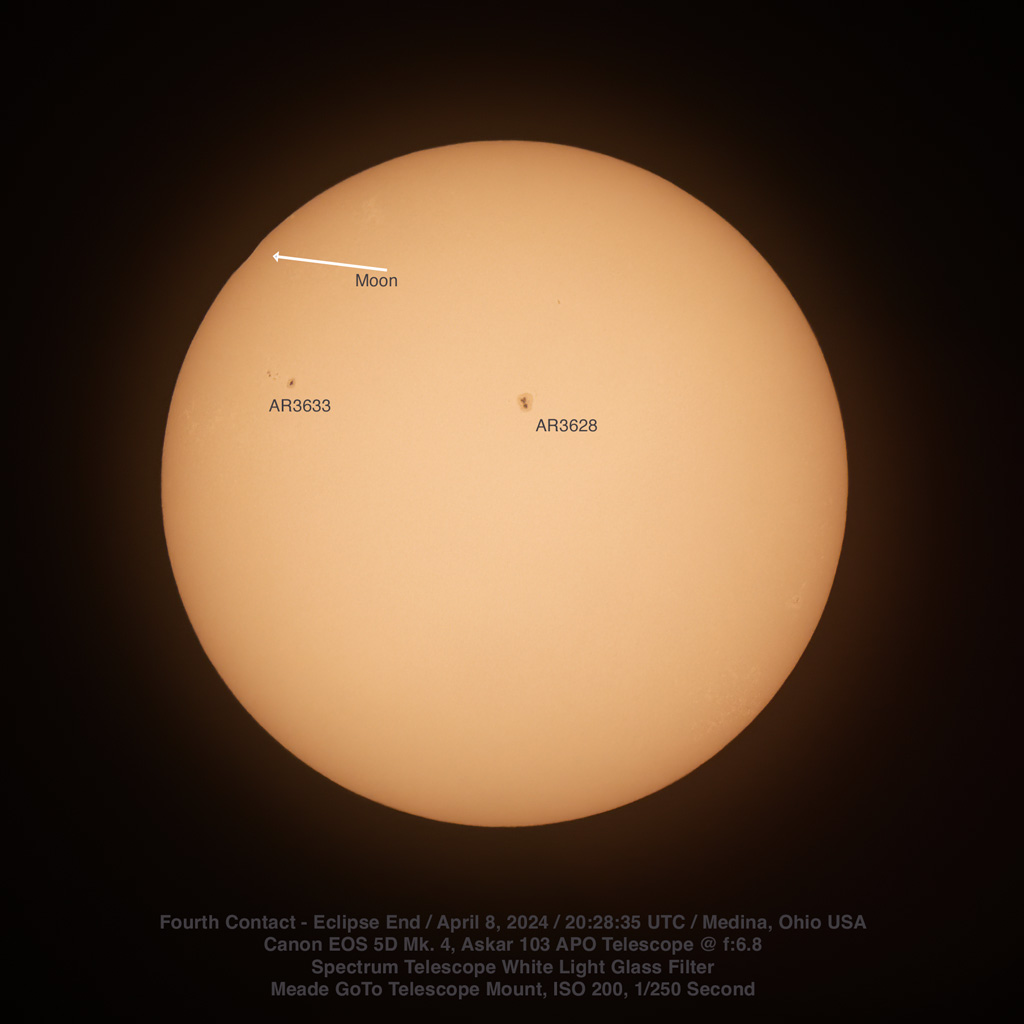

We began with the Askar 103 APO telescope and its 700mm focal length, attaching our Baader Herschel-Prism, and the new ASI678MM monochrome camera. The setup worked well but for one issue: focus was only just achieved with the focuser racked all the way in with no latitude for adjustment. Image quality was very good but probably would have been better if we’d have had a bit more inward travel. Note: It was only later that we realized we might gain the needed travel if we had switched the camera’s nosepiece from the 1.25-inch to the 2-inch, allowing removal of the thick 1.25-inch adapter ring from the Herschel. A well, duh, moment!

By the way, we continue to be impressed by the build quality and optical excellence of the Askar refractor. It’s a solid instrument with great features, delivering superb results.

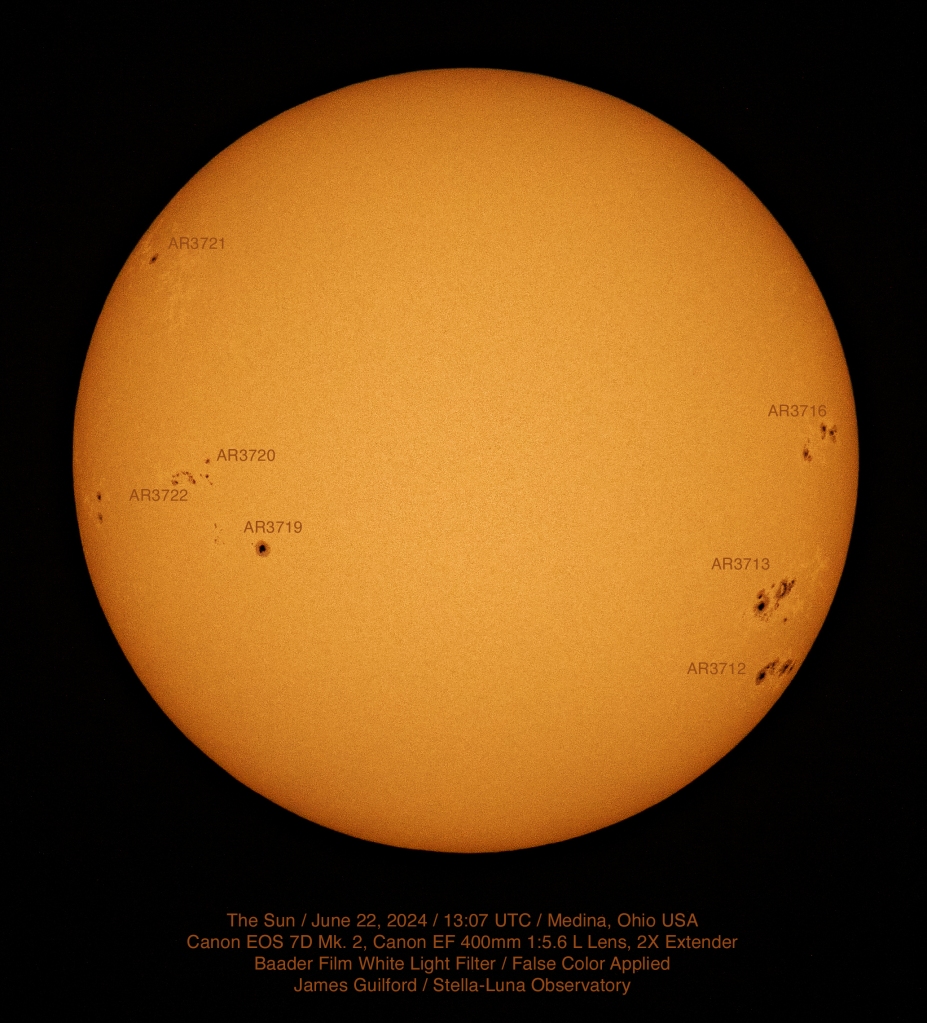

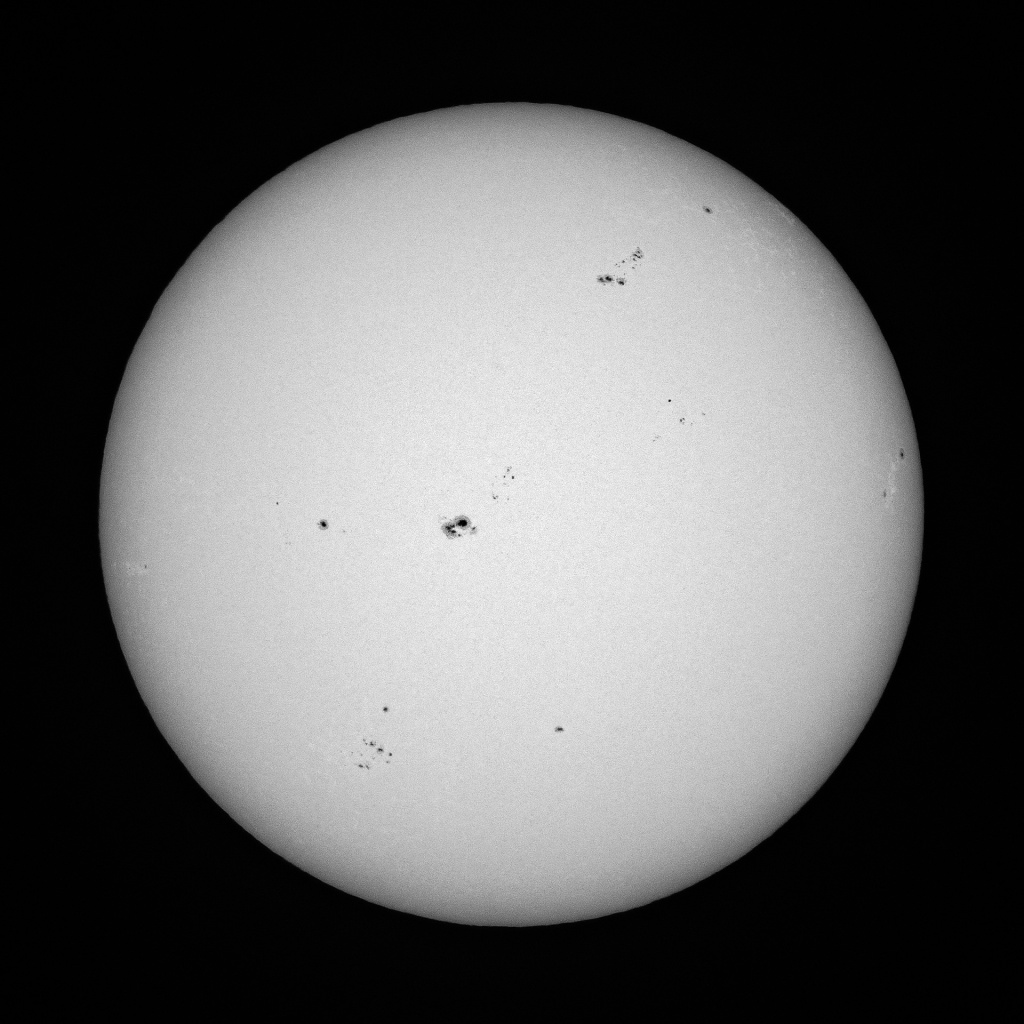

The second experiment involved installing our massive Meade 6-inch telescope on the mount. The Skywatcher has a retractable rod for holding counterweights and is, therefore, a bit shorter than it might otherwise be, resulting in less leverage. It took nearly all of our available counterweights to balance the big scope. We installed the Herschel-Prism and a nice eyepiece and got beautiful views of the spotted face of our star. Attaching the ASI678MM, however, we could not reach focus — that inward focuser travel limit again — but we don’t believe the switch to the 2-inch nosepiece will help. That’s a shame! The Meade’s 1,250mm focal length would have provided amazing closeups!

With the mount set up we decided to try out the 11-inch Celestron SCT at night. Herschel wedge accessories are not to be used on reflecting telescopes as the concentrated unfiltered incoming sunlight can damage the scope’s secondary mirror. To our disappointment the telescope, which has set in storage for months since we attempted collumnation, displayed rather severe image distortions — comma-shaped stars. After a good bit of frustration we dismounted the telescope and planned to come out the next night with the Vixen Cassegrain telescope.

The following evening looked very promising; the sky was actually more transparent than it had been for the Celestron effort. Saturn would rise from behind trees neighboring our site some time after 11 p.m. so, at the appointed hour, we stepped outdoors and looked. Clouds, heralding a day or two of rain showers, were rolling in — broken at first but rapidly obscuring the entire sky. We tore down the setup, stowed the gear, and called it a night.

Over the period of a couple of days and nights, much was learned and the new planetary camera proved itself to be an excellent performer. We’ll continue to use the camera and telescope for solar and, probably, lunar views. Next we’ll likely try installing the focal reducer to achieve full-disk images.